“There are two things that can happen with pain. You either transmit it or you transform it.” Tim Shriver, Founder UNITE, Co-Founder CASEL

The effects of transmitted pain play out in our communities daily. Children and youth who have experienced negative factors related to Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are more at risk of the pain from those factors leading to short term and long term trauma. ACEs family factors of abuse, neglect, poverty, mental illness, and violence are a part of this equation, but we also know that community factors play a significant role as well. “Communities with high levels of social and environmental disorders” (such as racism), communities with high crime and violence, high unemployment rates, unstable housing, and other social ills all factor into high risk factors of trauma for a student. The more factors a student experiences, the higher the risk for serious problems into adulthood, which can equate to significant trauma. Community factors affect family factors affect student factors.

Which can lead to a seemingly endless cycle of transmission of pain, from one generation to the next, including internal struggles of self-worth, identity, and belonging.

Left unchecked, student pain related to trauma will transmit itself frequently into the classroom and the school – teachers and staff bear witness daily. Discipline issues for everything from “acting up” in class to serious threats and fights, low or failing grades, disengagement, and low self-esteem and anger are not uncommon for students caught in the cycle of untreated emotional, mental, and physical pain. Not dealing with the pain, per Patterson, “is a slow walk to failure” for too many of our students.

And as we know, students are also grappling with COVID’s prolonged effects of social distancing, illness, and loss.

Our kids are going through a lot.

Of course, teachers and leaders, being who they are, have recognized the need to step in even more to do what they can during these trying times. They are reaching through screens to provide supports to kids through virtual check-ins, morning meetings, SEL lessons, and more. Indeed, they have indeed been in-person material deliverers, food deliverers, and hope deliverers.

Educators have been serving as those frontline adults, even pre-COVID, charged with addressing student pain and its consequences in school, in the home, in the community, and life.

“Our kids experience pain in their communities, in their homes, everywhere they turn.” George Patterson, Sr. Director My Brother’s Keeper, NYC Dept of Education

Breaking the Chain

So what are educators doing to support students who are living with trauma? Though the details can vary, we have seen common threads of success in schools. And they are doing this work and showing that we can break the generational “chain of pain”. Though not meant to be an inclusive list, three common threads should be in place in every school.

- Caring Adult – Am I worthy?

Does it get any more basic than this? Positive relationships are key for every student. The value of a student having at least one caring adult to go to for support, questions, and guidance is immeasurable. Educators (including support staff such as cross walk guards, bus drivers, cafeteria workers, and more) are critical to filling this role in schools. One example we have seen is the adult mentoring program such as My Brother’s Keeper NYC. This program is providing valuable connections of support to boys and young men of color through a city-wide initiative, partnering cross-sector with the schools, the district, and with others. MBK’s mentoring component is part of the work of The National MBK Alliance, laying out six life milestones that they hope to achieve. It’s critical work we are happy to support.

- Effective and Equitable Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) – Do you see the real me?

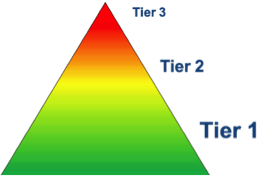

Most educators are familiar with the MTSS pyramid for academic and behavior supports across the continuum, including supports for the seen and unseen effects of trauma. Individual states and even districts put their own details into their MTSS models (formerly called RTI, Response to Intervention), but a basic “pyramid of support” ensures the following:

We know that Tier 1 components are for all students – they are the universal skills, knowledge, and tools that are of benefit to every child and youth in their health, well-being, and social emotional academic development. In other words, all students have access to Tier 1. Components should encompass such things as culturally responsive teaching and learning, social emotional learning (both explicit and embedded), student centered discipline and behavior supports, and more. Additionally, effective Tier 1 is of high quality, is age appropriate, and keeps student engagement at the forefront of implementation.

We also know that for those students who need more support beyond the first Tier due to a combination of factors (related to trauma or other factor), targeted supports at Tier 2 and Tier 3 should be made available to students who need them. Effective schools use such things as early warning systems, collaboration between home and school, data collection, and active monitoring of student progress. Other targeted strategies at these Tiers may include intentional peer or adult mentoring, small groups related to concerns (i.e., grief, divorce, other), self-monitoring tools, even testing and individual therapies as interventions intensify.

Many suggest that the increase in mental health issues is tied to social justice concerns and are calling for educators to take the lead in solving these problems that highlight the connections between race, gender, socio-economic status, and mental health concerns.

Ask most educators and they will tell you that while all MTSS Tiers matter (as well as the resources needed to do them well), they also know that getting Tier 1 right for every student is most critical. We simply know so much more about the interconnectedness of trauma, social ills, and the role schools can play in both…especially problems that can be effectively addressed for students at Tier 1 if done correctly.

One critical component of effective Tier I is ensuring a school embraces Culturally Responsive Education (CRE) as a fully committed approach. Students should not only see themselves in all aspects of teaching and learning, but importantly, should know they are also valued as a vital member of the school community – do they also see themselves in the displays & celebrations, the activities offered, the way parents are engaged, and more? These things are important for all students, but especially for populations that have been marginalized.

And, of course, putting the structures and supports in place takes intentionality by the adults.

- Professional Learning – How will you best support me?

Re-imagining how educators deliver Tier I takes training beyond learning a new curriculum or teaching strategies (though yes, those are KEY). It takes digging deeper so adults can reflect on their own practices and acquire the skills and knowledge to help support all students, most especially students dealing with the lingering effects of trauma that may not be readily seen. Professional learning in Implicit Bias, Restorative Practices, SEL, Trauma Informed Teaching, and a school-wide picture of CRE are just some of the “dig in” learning happening with educators across the country. Educators are making the internal shift to ensure their teaching aligns with appropriate external practices that better align with the students they serve. And along the way, they are also the ones now challenging long-standing curricula choices, ensuring that students not only see themselves in the curriculum they implement and the literature they promote, but they also are providing students with a fuller picture of history – the challenges and the contributions that better reflect the diversity that make up our country and world.

It’s a beautiful cycle of hope. When we know better, we do better.

We realize this work takes time and there is still much to do. There are no quick-fix solutions to overcome the pain of poverty, violence, hunger, and ism’s associated with race, identity, gender, and difference. There are societal shifts that must happen beyond schoolhouse doors and there are individual shifts that must happen, to both the heart and mind. But caring educators who are intentional with systemic supports for their students while also allowing students to be affirmed and seen, are shifting the life outcomes for their students for the better. And that, ultimately, will benefit us all.

Supports in Action – A deeper dive

You can see examples of supports in action that are aligned with equity, inclusion, and access across the MTSS Tiers. One exciting and recent project CWK Network helped bring to life was the creation of NYC Public Schools Mental Health Continuum Platform, “a school and community-based program for improving student mental health and wellness.” This digital resource provides a plethora of resources and informational videos on real-time supports available across the city and across the MTSS tiers. It is available in multiple languages, removing access barriers for many families that NYC Public Schools serve.

Other Transformational Measures Happening

When we think of schools and districts as hubs of transformation, a hot button topic that many are talking about is policing in our communities and schools. In recent years, we have seen schools beginning to address these issues, specifically the disproportionality of arrests, expulsions, and suspensions related to students of color, identity, and difference. We saw one example in 2015. During Defining US network educator Meria Carstarphen’s tenure, Atlanta Public Schools partnered to create A Comprehensive School Safety Plan to re-think their district’s strategy around school policing, and develop them more fully through the hiring of their own in-house police officers, as well as providing those officers targeted, on-going trainings in SEL, restorative practices, and more. This began an important shift in how police at the district’s schools interacted with staff, students, and parents.

And most recently we are seeing this shift in school policing take place in the America’s two largest school systems.

One of our network districts, Los Angeles Unified School District, recently announced reallocation of police department funding for an investment in school climate coaches, staff who will be stationed at all secondary schools (rather than a police officer) to “assist administrators and staff to support a safe and positive school culture and climate for all students and staff.” These new coaches will receive trainings in such areas as SEL, culture and climate, de-escalation techniques, implicit bias, and disproportionality in discipline practices. Police officers will still be available to respond to serious incidents that require direct police intervention, but the goal of this shift is to ensure that the first response is the most appropriate response to the situation.

Also, per LAUSD board action, additional dollars will be invested in a Black Student Achievement Plan, and will cover such things as the hiring of psychiatric social workers, restorative justice advisors, and counselors (resources for intervention staff as mentioned much earlier in this newsletter). These other resources will include “expanding diverse representation, inclusion of Black authors, and social justice connections”, professional development, community partnerships and more.

For another network district, NYC Public Schools, recent discussions have included moving their police officers, called School Safety Agents (NYC PD officers!), to the supervision of a department focused on access the department’s holistic trainings, including SEL.

Though these examples of changes in school policing are different in design, at their core we see a common agreement that adults who interact and work with students must have the skillsets, the knowledge, and the mindset (the smarts and hearts) needed for kids. Our students come with great gifts, but they also come with many challenges they bring with them from the traumas they face, both seen and unseen. A shift from punitive systems to more restorative systems is a must for their better life outcomes and another lever needed that can break the cycle of pain. We have hope that the larger community is watching, listening, and learning as educators lead the way in this important work.

“…if we’re really going to create a just nation, we have to bring transparency into the educational system, into who’s getting suspended and for what? Who’s getting expelled and for what? What color are they? What’s the socio-economics behind it…so it goes well beyond us.” Chief Art Acevedo, former Miami Police Department

Written By: Tammie Workman, Education Consultant and Former Urban Schools Leader with Stacey DeWitt CEO of CWK Network.