“The first time in my new school I read a sentence about black Americans in a textbook the sentence read – I was nine years old and this is what sticks with me – ‘Black Americans live in ghettos’.”

Dr. Sharon Contreras understands firsthand the importance of education. As a young Black girl growing up in Long Island, NY, one of 10 siblings, the importance of getting an education, and especially learning to read, was understood as the primary way to a better life. Neither of her grandparents could read, as they spent their youth working long days in cotton fields rather than being in school; they, along with her parents, “pushed” Contreras and her siblings to place high value on getting an education. It led Contreras to life as an educator, leading to her current position as Superintendent of Guilford County Schools (home to 73,0000 students) in Greensboro, North Carolina. Dr. Contreras gives credit to her family for the understanding of the “long history and rich history of African Americans. We have always struggled for education and understand that education leads to liberation.”

This knowledge of her forebear’s history, not only the darkness of slavery, but the many accomplishments and joy that was part of the full fabric of African American life, became doubly important when Brown v. Board deemed segregated schools unconstitutional, paving the way for integrated schools in 1954.

Contreras, and other African American students with parents who understood the need to teach their children the full history of their race and culture, was fortunate. She recounts the time she was “not a princess” for the Halloween parade, but rather chose Phyllis Wheatley, the first African American poet to be published. And she also remembers the time she gave her first book report in her new school, when she chose Daniel Hale Williams, the African American doctor who performed the first successful heart surgery. Her sense of self came not from her school, but rather from the continued “push” by her parents and grandparents to know and value her history and the many accomplishments of those who came before.

In those early and later decades of desegregation, other parents of African American children kept this fuller history alive outside of the school, through immersion of Black culture in the home, the church, and the expanded fabric of the Black community.

Phyllis Wheatley, the first African American poet to be published

In a recent article for The Atlantic, writer Michael Harriot also detailed his experience as a Black child growing up in South Carolina during the 70’s and 80’s. Harriot’s mother homeschooled Harriot and his sisters during their elementary years as a vehicle for them to realize their full potential as Black children growing up in a white world; their young lives were steeped in Black culture and Black experiences. He recounts, even given the vestiges of broader segregation, that the family intentionally had little interaction with white people and were shielded from negative images and depictions in books, films, and other cultural items deemed too white, too demeaning, or downright racist. Recanting this time, he states, “A few years ago, I asked my mother why she put so much effort into concocting this Caucasian-free cocoon. She informed me that our childhood was part of an experiment she had envisioned before we were even born. ‘A Black person’s humanity can never be fully realized in the presence of whiteness,’ she explained. Not a single day has passed since in which I have not thought about that sentence.”

The Divides We Face

Both Contreras and Harriot’s experiences, though quite different, highlight the importance African American history had to their overall development as they grew into adulthood. Their parents recognized this importance and were there to provide their children with their fuller histories, beyond the tragedies to the triumphs as well.

Humans yearn to be known, accepted, and seen by others. It’s in our nature to want these things. When we better know the true picture of ourselves (our histories, our place in the world, our struggles, and our achievements), then it stands to reason we can better understand, appreciate, and accept those around us, including, ultimately, how their place in the world relates to our own. To better realize each person’s unique potential, we need the fuller picture of everyone.

Thankfully today, there is a broader push for schools to provide their students a much more comprehensive and inclusive view of the themselves and others. This approach is commonly referred to as Culturally Responsive Education (CRE) and it is happening across America each day. Educators, through expectations messaged from their districts and states, including opportunities for professional learning, are awakening to the importance of CRE in their students’ development and well-being and are delivering on it for the students they serve.

Culturally Responsive Education (CRE)

So, what is CRE exactly? Through CRE (also referred to as CSE – Culturally Sustaining Education), educators are giving students access to curriculum, teaching methodologies, and resources that are centered in their students’ identities, heritage, language, and experiences. At the same time, they are building their own understanding of themselves, including their personal biases, fears, and the intersection of both within their classroom.

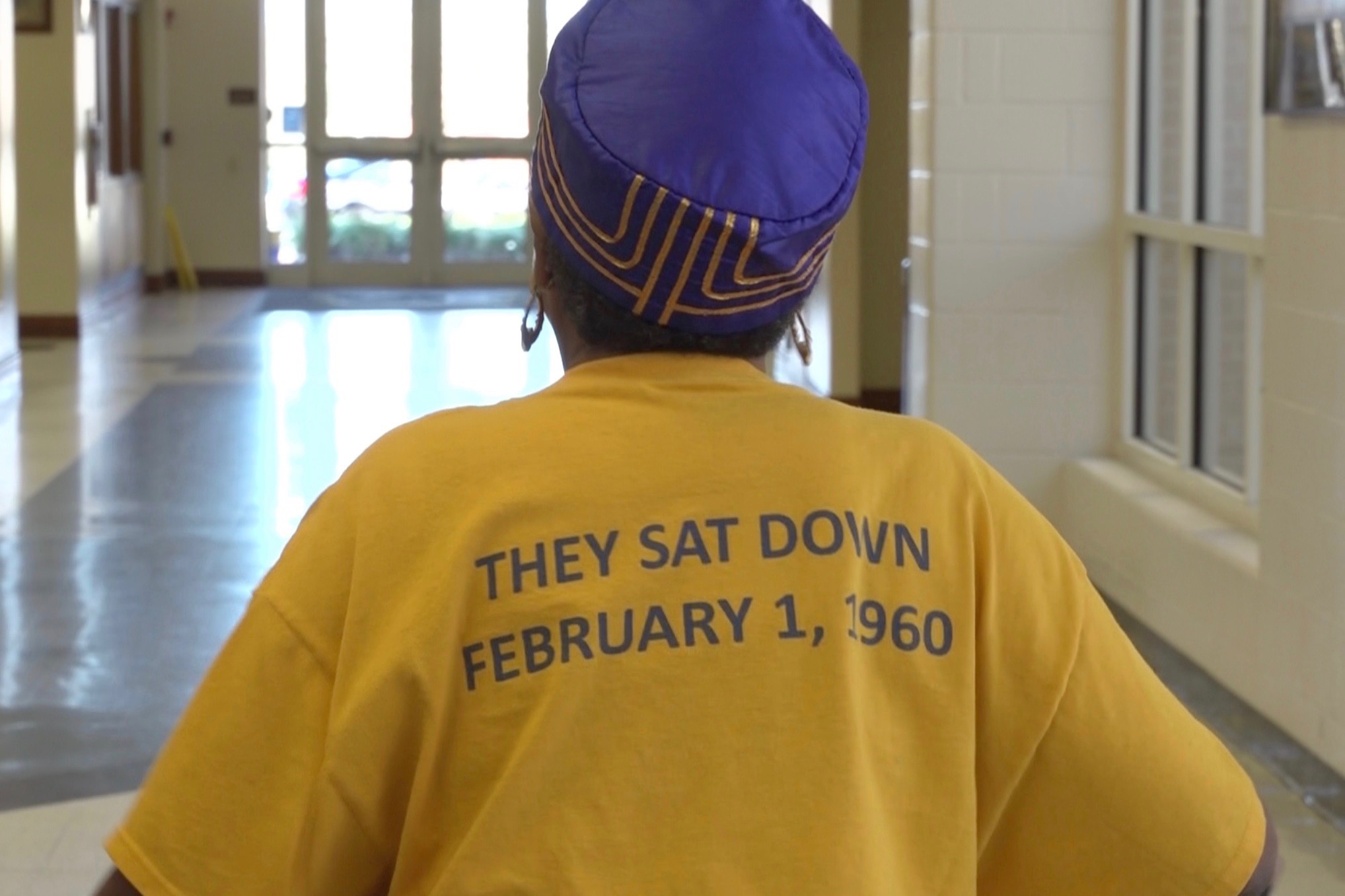

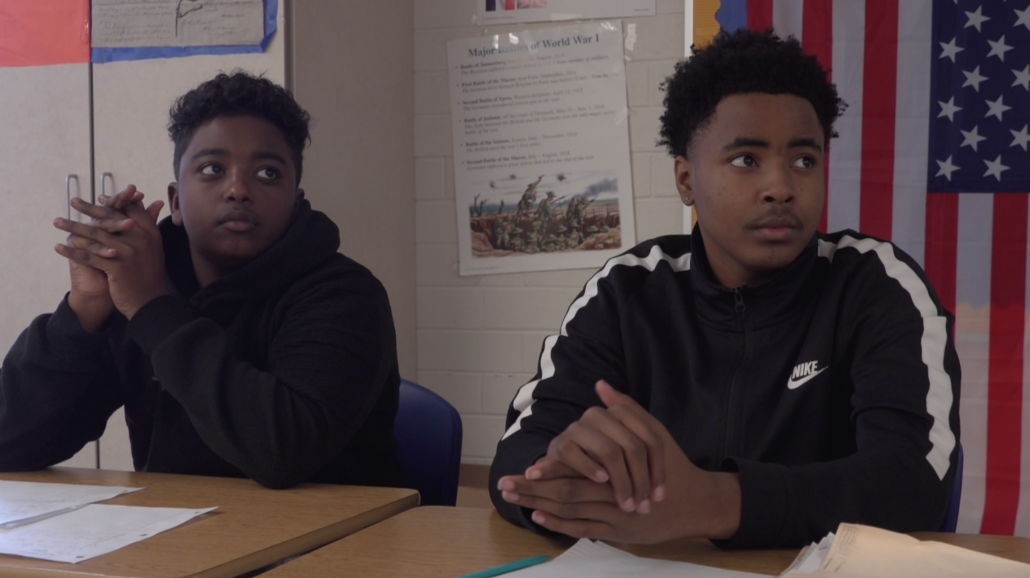

COVID-19 constraints aside, one recent example of CRE in action that we found valuable, can be found in Guilford County School’s James P Dudley High School, through Social Studies and Freshman Seminar teacher Nicholas Hutton’s classroom. In the class, freshman males learn leadership, life skills, and the tools to become successful and emotionally healthy members of society. Additionally, according to Hutton, “they spend the first few weeks of the semester covering the history of Dudley. So, everybody from James P Dudley to Dr. Tarpley to the Civil Rights movement are really emphasized. Dudley is the heart of the Civil Rights movement basically in the Southeast. Think about the sit-ins, they all started here. We start with some background about the school. There’s no civil rights movement. There’s no successful football team, there’s no community activism, there’s no A & T without James P. Dudley. He is the one who helped start all of it…. So, once students know that their history is something they can touch, if they are in the hallway, in the library, they come in here and they can see figures that help inspire generations throughout the community. And as a relation to manhood, it goes against the stereotype.”

And students notice. As Dudley freshman Jordan Blackstock noted, “I didn’t know that (Dudley) was a person’s name and I didn’t know the history behind it. I think it is important. He was Black like us.”

Superintendent Contreras puts a fine point on why knowing the history of ourselves and others is important for everyone.

“Culturally Responsive Education is education that meets the needs of all students. It does this by being inclusive, by embedding the history in culture and language of the students that are served in the curriculum and by making sure that teachers understand the culture of the student and are able to respond to students appropriately. Adding cultural competency and adding student history and culture to curriculum has a statistically positive impact on student achievement and will help us close those persistent achievement gaps. So, it does matter to let young people know who they are.”

Contreras understands that not all schools in America are there yet with ensuring their students feel safe and valued and seen. But she does “believe public schools may be the last platform that has a common audience in their community where they can lead this work.” We believe this also.

Where we stand now is not new. We recognize the challenges that lie ahead and there are no quick fixes or one single approach to fixing our ills. Strong legislation that tackles inequities and perpetuates our division is certainly one thing needed across multiple sectors. But we also know, along with strong policies, we must also inform minds and change hearts at the same time – with students and adults. We believe that our educators are on the cutting edge of showing us how through practices such as CRE that recognize and celebrate everyone’s unique heritage. These educators are building future generations that can indeed help bridge the things that divide us.

“If a race has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated,” Carter G. Woodson, The Mis-Education of the Negro, 1933

Want to see more on how districts such as Guilford are doing this important work?

Dr. Contreras’ district has much good happening in Culturally Responsive Education (CRE). Check out their Diversity and Inclusion Homepage for links to the vast resources they are providing to educators, parents, and their community. One example can be found at the Native Knowledge 360 webpage, full of resources on Native American History and Culture. We applaud this inclusion of necessary resources from one of our valued partners; this resource is one of many examples of how Guilford County Schools is leading the way on CRE!

A parent’s perspective on the value of CRE

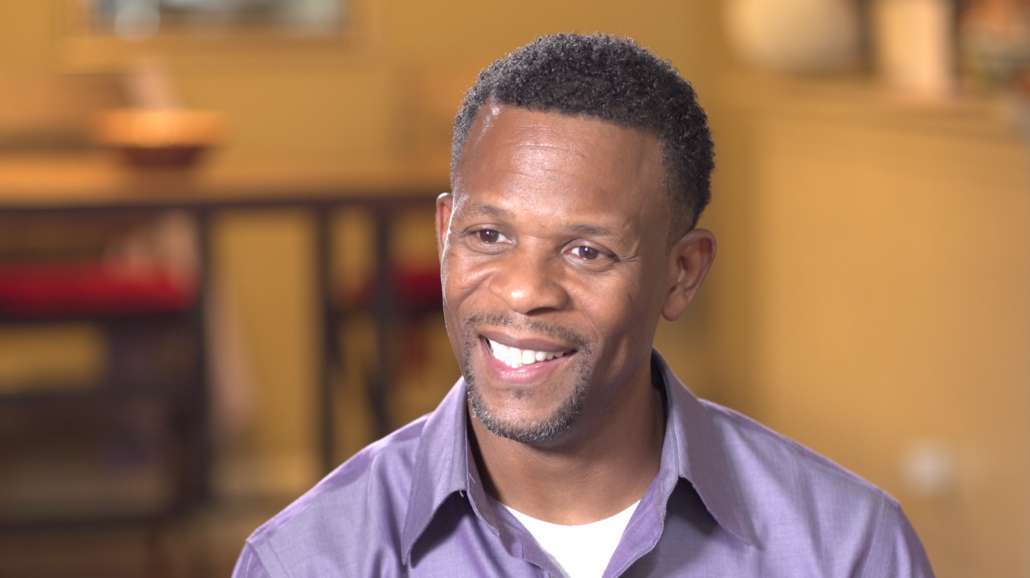

Charles Brant, former Grady High School parent, is one of our featured “parent experts” in the upcoming first documentary for the Defining US series. His is an important voice and perspective on the importance of valuing and knowing each other’s histories. To the right is a small preview of what you will see and hear in the film.

“I think when you study history and any great civilization, any country of people, talk about the significance of history and the importance of knowing who you are, I think that’s important on a number of levels. I think it’s important individually. I think it’s important culturally. I think it’s important for a lineage where you fit. What has transpired with you as a person, as a people and where do you fit in this great world community? How did you get here? And I think history is a map to all of that… I think is necessary for all people to have things to be able to refer back to and see that they’ve contributed to the world order and how we got to where we are.”

Written By: Tammie Workman, Education Consultant and Former Urban Schools Leader with Stacey DeWitt CEO of CWK Network.