By Guest Blogger: Alison Yoshimoto-Towery, Chief Academic Officer, Los Angeles Unified School District

Originally published in the LA Times parenting newsletter “8-to-3″ reprinted with permission.

I had the best kindergarten teacher. He was never far from his banjo or guitar — he would lift the embroidered strap over his head, tighten a string or two, then play folk songs from memory. To this day, I can break out into a full-throated chorus of “This Land Is Your Land” with ease and sentimental pride. I shall definitely do that on Independence Day 2021.

On this Fourth of July weekend, let’s remember that true independence has not always been afforded to all in our nation. The language and attitude of opportunity is a birthright for some, learned by others and fought for by many. For most, the route to real independence is through a high-quality public education. Our nation’s future requires that we build and maintain a public education system that gives every student a pathway to thrive in life and find a place as a part of a greater community, for the betterment of all.

The deep inequities highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic, the murder of George Floyd and the rise in hate crimes highlight new urgency for an interdisciplinary, well- rounded education. Solving complex problems creatively, working collaboratively with others seemingly unlike ourselves, and thinking critically about information is a right that must be afforded to all — and is as important as reading, writing and mathematics. Using knowledge and skills gained through inquiry can be used to be civically engaged, bring joy to others and demonstrate our interconnectedness.

In my position as the chief academic officer for Los Angeles public school students, I see how there is no stronger evidence of our country’s historical injustices than in the opportunities that have been systematically denied to many students because of intergenerational poverty, lack of access to education and basic services. It is through public education that we repay the debt owed to those we as a country have historically oppressed. Through my own family’s experience, I understand the roots of systemic racism and the need to actively address its long-term effects.

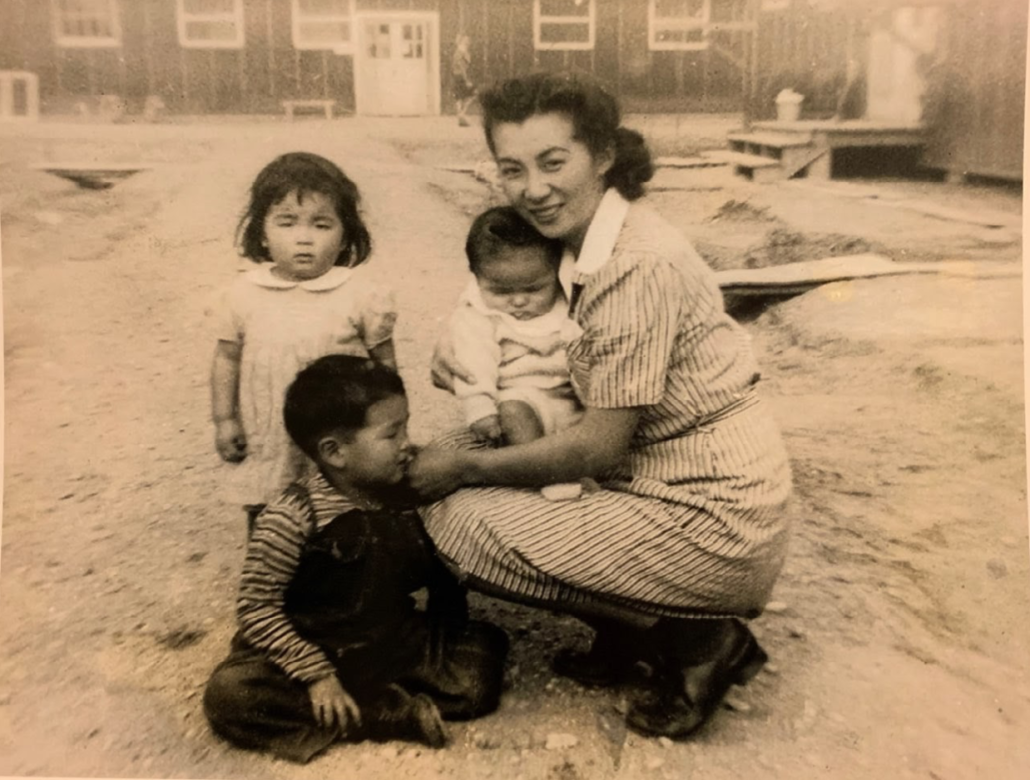

Frances Tayeko Yoshimoto, the grandmother of Alison Yoshimoto-Towery, is pictured with her children, from left, Yuki, Miki and Keibo. The 1943 photo was taken at the Jerome, Ark., internment camp. Keibo is Yoshimoto-Towery’s father.

My grandmother was alone in 1942 at Los Angeles County General Hospital when she gave birth to my father. Her husband, my grandfather, and their two toddlers, had been taken to an internment camp near Jerome, Ark. Twelve other strong Japanese American women, whose families were also forced to leave them behind, were with her in the hospital. When the 13 babies were born, the infants and their mothers were put and taken to a desolate camp surrounded by barbed wire because the government — our country’s government — feared their ancestry.

My other set of grandparents, mere teenagers, fled from the Manzanar camp to Chicago in 1945. My mother was born just after the war, on Chicago’s South Side. Her first crib was a dresser drawer. It’s where my mom learned that it was safer for American people of Japanese ancestry not to look Asian or speak their parents’ language, but instead to keep their heads down, work hard and stay quiet.

How does one not look or act Asian? Growing up, all of the female role models in my family had red hair. Most Japanese Americans of my generation were encouraged to speak only English. My grandmother, having faced so much hatred herself, did her best to protect first my mother and then me by having us wear a clothespin on our noses in the hopes they would look thinner and more Caucasian, and by having us pull our eyelids 10 times a day to get a double eyelid, a second crease above the eye.

This experience is not unique to Japanese Americans. Children of diverse backgrounds are judged by mainstream expectations — cultural traditions, language spoken, hair styles, eye and skin color, learning differences, sexual orientation, gender norms, and even clothing or lifestyle. Feelings of motivation, connectedness and emotional safety are directly correlated with whether students feel seen, heard and respected, or see others like oneself in positions of influence within their environment.

As migrant workers on chili and sugar beet farms, in cannery and sewing factories, and in auto mechanic shops, my family’s pathway to independence was through public schooling. It took four generations before my brother and I were the first to graduate from a four-year college.

Every child arrives at the school gate with assets — even if they are not the strengths traditionally valued. For example, 90,000 students in Los Angeles are learning English, 14% of them new to the United States within the last three years, with an incredible gift of being or becoming multilingual. Yet, to the contrary, the federal term used is “limited English proficient,” rather than acknowledging a strength. Another 180,000 students in Los Angeles schools who are African American/Black, Latino, Pacific Islander or American Indian/Alaskan Native are learning in school “standard” English, which can be different from the form of English spoken at home. Yet, the home language historically has not been valued at school, even when it is an integral part of a child’s identity and is a way of communicating that carries great power. A child being told “that’s wrong” or “incorrect” when that’s the way their family may speak sends a clear message of who and what is valued.

I am inspired daily by the hardships overcome by our students and their families and share in their triumphs. Each personal story strengthens my mission, deepens my empathy and renews my sense of urgency. I believe every young person can and will be successful when given the proper support and safety nets. We must do whatever it takes to reach that success even if that means evolving our own understanding, including changing — or even letting go of — a practice or policy in the systems we represent.

On this holiday I have reflected on the many courageous American immigrants who have sworn an oath of citizenship. Many others have led protests or gone to court to ensure equal freedoms were afforded to all. I think of the recently coined adage that ours is a country where “Rosa sat, so Ruby could walk and Kamala could run,” referring to civil rights icons Rosa Parks and Ruby Bridges paving the way for Vice President Kamala Harris. I think of Los Angeles students who attend three schools a year because their families are migrant workers; the estimated 10,000 students in the Los Angeles Unified School District who do not have stable housing. I think this is neither independence nor freedom.

For our students, this means that our collective work ahead includes giving every child exceptional academic, communication and collaboration skills — in multiple languages and settings. It means examining our practices, our own biases and our own beliefs to help every child be proud of their family, culture and identity, and to have a trusted, caring adult to encourage, inspire and sometimes say: “I care about you. I expect more of you. I believe in you.”

Yoshimoto-Towery’s great-grandparents and other family members work on a chili pepper farm in Garden Grove.

These goals will take more than educators to accomplish. We need partners from throughout the nation to give students some of the resources that are beyond their reach, inspiring them to become a reader, writer, engineer, historian, artist, scientist. It means incentivizing careers in education, surrounding our schools with industry opportunities to teach our students how to solve problems through inquiry; providing internships, field trips and summer jobs; and providing every student with a mentor, tutor and caring adult to guide them toward financial independence, postsecondary options and self-driven life. Each student deserves a joyful and engaging way to connect with their education to ultimately make the world a better place.

On this day of independence, we not only celebrate the past, but call to action the work of today and tomorrow. Let’s find a way to make “This land was made for you and me!” a reality for each and every young person. We owe it to them.