By Jennifer Saunders, School Library Media Specialist for Atlanta Public Schools and President of Georgia Federation of Public Service Employees.

By Guest Blogger: Jennifer Saunders, School Library Media Specialist for Atlanta Public Schools and President of Georgia Federation of Public Service Employees

You know when someone tells you NOT to do something, you almost instinctively want to do it? Maybe it’s just me, but when I see orange cones in the street, nicely spaced apart, directing the flow of traffic as silent sentinels, if they are slowing down my route, I get this secret desire to weave in and out between them or even move them out of the way, slightly re-arranging them so I can keep going. This happens especially when I’m in a hurry or know my route has just taken a longer turn due to those cones. Luckily for the public good, I don’t do this because I understand their purpose – as a common good, guiding me and others to our destinations.

If you think about it, books are sort of like those orange cones. Placed on shelves in schools everywhere, they are also there to help guide the way for millions of students to self discovery, fanciful journeys, historical truths, and information just waiting to be absorbed. But sadly, as we all now know, books have become those objects that are now being moved out of the way, without thought to how any re-arrangement or removal could have ripple effects for students. Somehow, either due to the isolation of the pandemic or the political divide or both, books in schools have become a new lightning rod for debates happening about schools in states across the country. The artistic, creative genius of writers who have the intellect and courage to capture their thoughts, whether they be based on real-life experience or their imagination, has been deemed inappropriate, challenged, and banned in various parts of our country.

My immediate reaction to banning any book is, “How dare these people? What gives anyone the right to say what a person can or cannot read?” As a Black woman whose great-great grandmother was enslaved on a Georgia plantation, denied freedom to choose, this feels not only uncomfortable and wrong, but a glaring example of why we all need to fight against banning books in our schools.

So I’ve begun to dig a bit deeper into the types of books that are actually in the crosshairs of legislators and school boards today. And actually we’ve been here before. In the early days of my teaching career, I remember when a specific book series was banned from some schools and districts because of the heavy presence of fantastical wizardry. I personally loved these books and had many students who also loved them as they were pure escapist fantasy, allowing readers to escape their routines and spend time in a world that didn’t exist in real life.

So why would this book be a banned book?

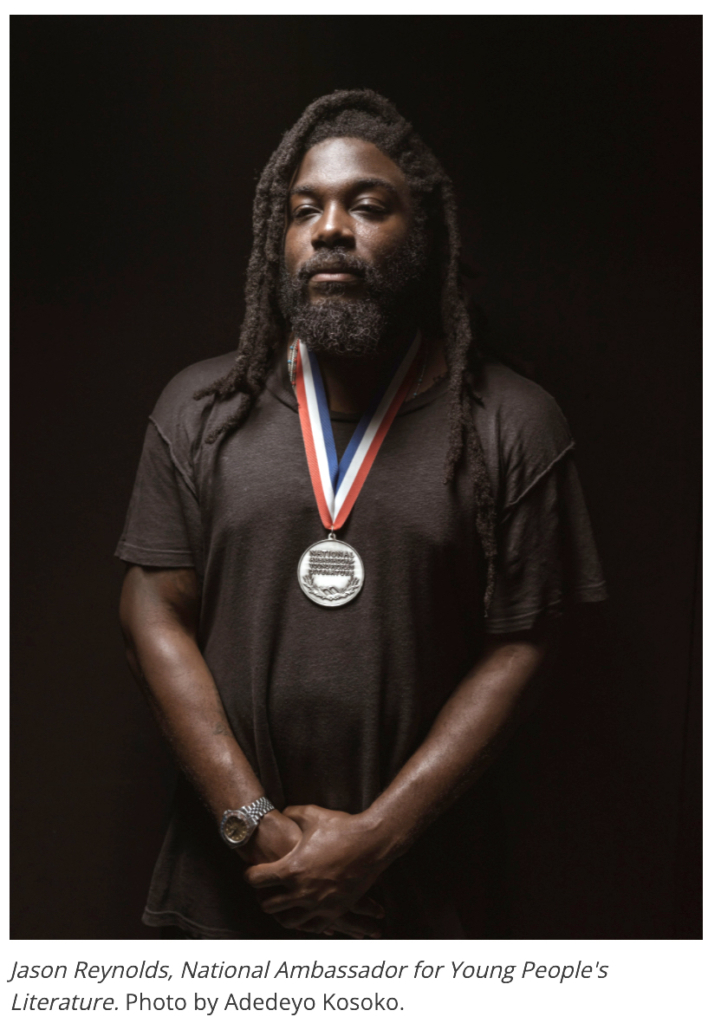

But when I look at many of the books being banned today, they are actually based on things that can happen in real life or on the actual experiences of real people. Books such as George, Speak, Something Happened In Our Town: A Child’s Story About Racial Injustice are among the top 10 most challenged books of 2020 according to the American Library Association. Also included in this list is All American Boys. One of the two authors of this book, Jason Reynolds, who is the current National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, has written books that widely promote the experiences of young Black boys and Black girls in urban settings. He has said that his books are a love letter to Black kids and that he writes them to acknowledge their presence in this world. All American Boys tells the story of Black high school students and how they experience and deal with racism and police brutality in their lives. In it, we read the story of Quinn, a White student, who saw his best friend’s older brother, who is a police officer, brutally beat one of his classmates, who is Black. And though the book is a work of fiction, we all know through the news, social media, and if you are Black, that this isn’t fantasy, but a scenario that can and does happen in real life. I attended high school in a suburb of Philadelphia and when I think back to my own high school years, the experiences of some of my Black male classmates and even my own brothers actually mimics many of the elements of the fictional tales in All American Boys.

So why would this book be a banned book? In Sewanhaka (NY) Central High School District, parents objected to this book being on the 2021 summer reading list because a Black teen was beaten by a police officer. The parents further felt that students should be focused on “being kids”. As a mother of two Black young men, yes, I agree, it would be great to be focused on just “being a kid”. But we know that this is not reality for most Black boys in America and these types of encounters can and do happen. As do instances of bullying, exclusion, and violence against LGBTQ+ students, students who have a physical or learning disability, a mental health issue, or who may live in a family whose lifestyle is perceived as “different”. I’m sure these students too would love nothing more than the ability to “just be a kid”.

I want all students who are faced with negative experiences based on who they are – racially or other identity marker – to have access to books they can actually relate to and that speak to them. I want them to see themselves in books and I want books that can help spark healthy conversation about the actual real life events that they, their friends, family members or someone else they know encounter in their lives. I want books to help them process all of the negative happening around them to find their way through to a better place so we can all get to a better place. As a mom, I want my boys to access any resource that helps them better navigate what it means to be a Black male in America. And as an educator, I want the same thing for any student who needs relatable material to read.

So why care and why is all this talk of book banning dangerous? Jason Reynolds, an author I highly respect, reminded an audience recently that banning books may cause the child who needs the book the most to not have access to it. Mr. Reynolds said, “We claim that we want our children to grow up and be better than we are and in order to do so, they must have the information that we did not have. So to stop that information, really makes us all hypocrites.”

I challenge each of us to think about the kind of child we want to develop and prepare for life in and out of school. Do we want children who are better than we are? Do we want children who are empathetic to another’s experience? Do we want children who see themselves reflected back in books they read and understand that others have those same experiences as they do and actually can come out on the other side stronger or better able to move forward in the world? Books such as All American Boys, Maus, Stamped, The Hate You Give, or Dear Martin can provide those avenues of understanding. Limiting access to books such as these doesn’t make the problems go away. But it does impede solutions to very real problems our students are dealing with in their lives and can possibly solve as they grow into adults. Why wouldn’t we want to elevate everyone’s humanity so we all feel we belong and that we all matter?

Scholar Dr. Gholdy Mohammed calls for educators to teach critically, “…to connect their teaching to the human condition and to frame their teaching practices in response to the social and uneven times in which we live.” (Muhammad, 2020) Without having the first hand experience of every human condition possible, books are one way to experience conditions outside of our own. They help us become responsive to the differences in each of us.

Sometimes the very thing you should NOT do is the exact thing you want to do. Just like the orange cones that serve as guides while we navigate driving and can be tempting to circumnavigate, we need to fight the urge to move books out of the way and out of the hands of students. They are there to help our students successfully reach their own destination in life.

References

Muhammad, G. (2020). Cultivating Genius: An Equity Framework for Culturally and Historically Responsive Literacy. Scholastic.

1 Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 51, 2000/Maccoby, pp. 1-27

“Parenting and its Effects on Children: On Reading and Misreading Behavior Genetics”